Breaking the News: Silencing the Media Under Martial Law

An important feature of any democracy is the free circulation of information. For people to properly assess what is happening in the country, what their leaders are doing, and how all these affect them, they have the fundamental right to obtain and engage this information. Forms of media like the newspaper, radio, and television play a vital role in ensuring that key information reaches the people.

As they carry out their duty, journalists that report on the activities of government, businesses, and civil society may often expose errors and even wrongdoing by certain individuals and groups. This is also important to democracy: freedom of information also entails freedom to criticize. This allows citizens to make better choices when it comes to selecting their leaders, and it even challenges leaders to perform their duties better with competence and integrity, knowing they will be held accountable to their people for what they say and do.

In his ascent to power, Marcos was well-aware of the role that the media played in society, and he exerted considerable effort to exercise control over it. By shutting down competing voices and setting up a media outlet that was under his control, Marcos silenced public criticism and controlled the information that the people had access to. By doing so, Marcos had the final say in whatever passed for the truth.

On September 28, 1972, Marcos issued Letter of Instruction No. 1, authorizing the military to take over the assets of major media outlets including the ABS-CBN network, Channel 5, and various radio stations across the country. This was within the first week of his declaration of Martial Law.

As justification for this mass sequestration of media assets, the Letter of Instruction cited the involvement of these media outlets with the Communist movement. Specifically, Marcos accused mainstream media of discrediting the administration, by propagating news that exposed its weaknesses to feed the flames of the Communist movement.

In the Letter, Marcos states that these media outlets were:

engaged in subversive activities against the Government . . . in the broadcast and dissemination of subversive materials and of deliberately slanted and overly exaggerated news stories and commentaries as well as false, vile, foul and scurrilous statements and utterances, clearly well-conceived, intended and calculated to malign and discredit the duly constituted authorities, and thereby promote the agitational propaganda campaign, conspiratorial activities and illegal ends of the Communist Party of the Philippines . . .

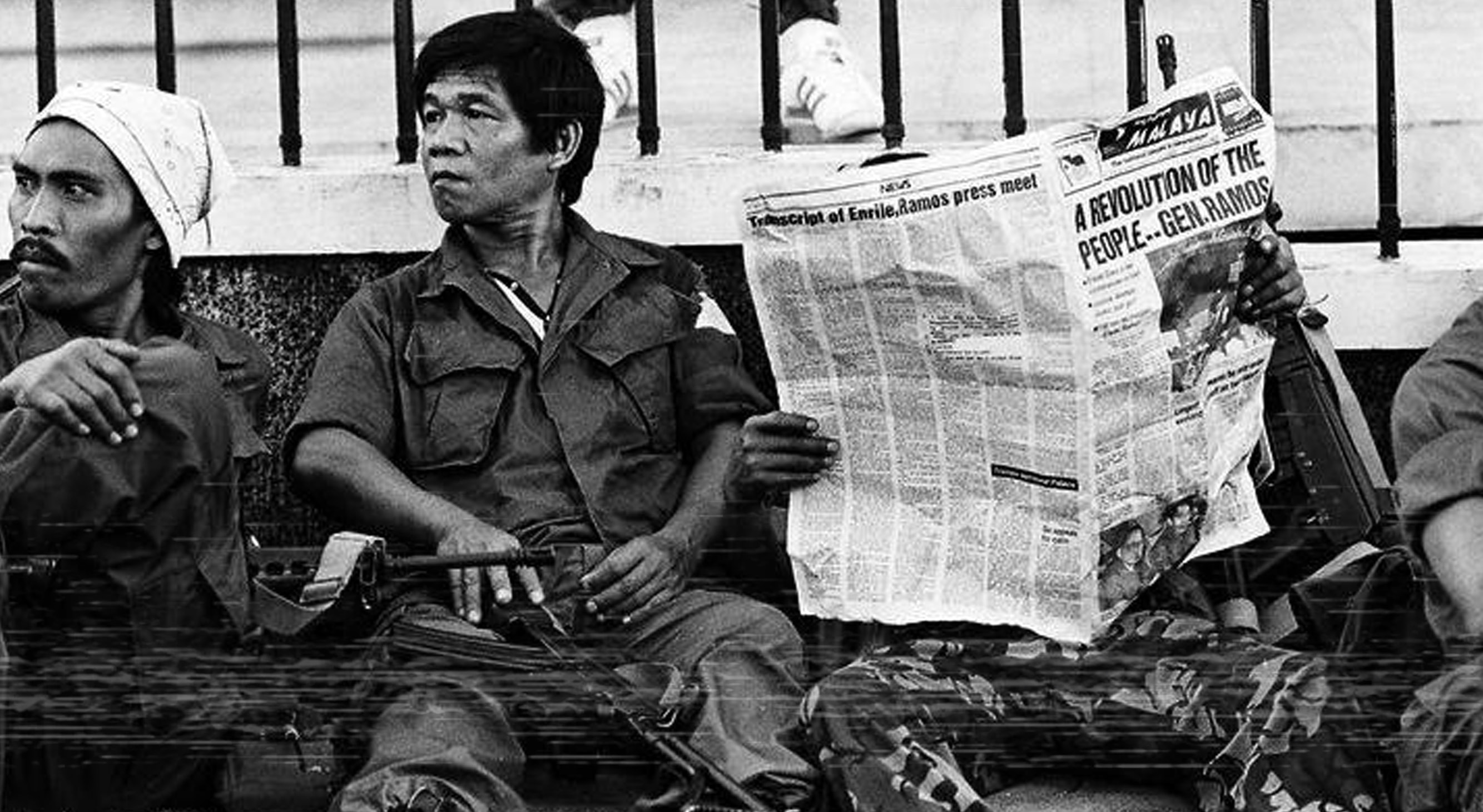

Teodoro Locsin, Sr., publisher of the Philippines Free Press, was arrested and imprisoned on the first week of Martial Law, along with Manila Times publisher, Chino Roces, and several well-known journalists including Amando Doronila, Luis Beltran, Maximo Soliven, Juan Mercado, and Luis Mauricio. On the night of their arrest, the detainees were led to a room by Col. Generoso Alejo where they were met by then Philippine Constabulary chief, Fidel V Ramos, who told them:

Nothing personal, gentlemen. I was ordered to neutralize you. Please cooperate. We’ll try to make things easier for you.

So how did people receive their information during all these shutdowns? Were all the media totally wiped out?

Not quite. In fact, amidst the news outlets being sequestered, some were still allowed to continue running print issues and airing shows on the airwaves. These included the Philippine Daily Express, the Kanlaon Broadcasting System, and several television channels. However, it is important to note that these remaining media outlets all belonged to Marcos cronies. Roberto Benedicto, for instance, owned Kanlaon and the Daily Express, while greatly enjoying Marcos’s favor as his appointed chairman of the Philippine National Bank, ambassador to Japan, and head of the Philippine Sugar Commission.

Primitivo Mijares, who served as Chairman of the Media Advisory Council, was Marcos’s top media man and propagandist. As chair of the council, Mijares had the power to dictate and censor content in all forms of media. In a change of heart, he confessed in a 24-page memo to the US House International Organizations subcommittee how he had aided Marcos in silencing media stories that exposed government abuses while fabricating others that would trumpet the administration’s supposed successes.

Primitivo Mijares. Photo by Elaine Ko, 1976.

In the memo, Mijares especially discusses how Marcos created an atmosphere of danger to create the pretext for the declaration of Martial Law, including but not limited to: having the military explode bombs during demonstrations, planting explosives in civilian areas which killed innocent bystanders, and threatening election personnel and members of the Constitutional Convention with violence. On the other hand, all this violence was blamed on the Communists, whom they alleged had received special assistance from foreign powers to support a government takeover.

The Media Advisory Council continued to play a vital role with Martial Law in full effect. In October 1972, when the Supreme Court was reviewing the factual basis for Martial Law, Mijares published a series of stories on New People’s Army rebels amassing by the thousands in the hills around Manila. In December 1972, when Marcos got wind of opposition to his proposed Constitution, Mijares published articles attacking specific delegates and legislators as destabilizing the government. In August 1973, when Marcos and his cronies could not get control of the Lepanto Consolidated Mining Company, Mijares also fabricated allegations of stock manipulation and fraud.

On September 20, 1974, Marcos appeared on the NBC Today Show told viewers: “There is no censorship at present.”

References

-

Letter of Instruction No. 1. The Official Gazette of the Philippines. Retrieved from http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1972/09/28/letter-of-instruction-no-1-a-s-1972/

-

Mijares, P. (1976). The conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. New York: Union Square Publications.

-

Pinlac, M. (2007). Marcos and the press. Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility. Retrieved from http://cmfr-phil.org/media-ethics-responsibility/ethics/marcos-and-the-press/