Young Marcos

Introduction

Before his meteoric rise to power, Marcos grew up as a young Filipino full of brilliance and promise. Well-loved by his family and community, the young Marcos had many admirers and supporters even at an early age. Many believed he would achieve great things in his life someday.

However, as it turns out, the young Marcos also had dark days to mark his personal history. These also played a role in shaping the man that would someday become President of the Philippines.

The following exhibit examines key events in his early years as a point of reflection on how they may have shaped his later actions in the political sphere. By seeing both the good and the bad in Marcos’s early life, sifting through facts and myths, it becomes possible to see the would-be dictator in a new light.

Early Life

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos was born on September 11, 1917 in Sarrat, Ilocos Norte to teachers Mariano Marcos and Josefa Edralin-Marcos. Growing up, the young Ferdinand was greatly influenced by his parents’ background in education and their austere demeanor. His biographies write of how he displayed a love for books and excelled in his studies; he was also said to be a quick learner and a great orator even at a young age. Nonetheless, the young Ferdinand is also depicted with a more playful and mischievous side. Though Ferdinand was mostly bookish and studious, he was also fond of sports, playing outdoors with his younger brother Pacifico, and pistol shooting.

From 1923 to 1929, Ferdinand attended three different elementary schools due to the demands of his father’s emerging political career as representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte. He first studied at the Sarrat Central School and later transferred to Shamrock Elementary School when his family moved to Laoag. When his family settled in Manila, Ferdinand completed elementary school at Ermita Elementary School, where his mother also taught. Ferdinand completed high school at the UP High School and later attended law school at the same university, graduating cum laude.

As Victor Nituda writes in The Young Marcos, Ferdinand showed great promise even during the early years of his childhood. In one account, Nituda narrates how Ferdinand, at only four years old, could already read the English alphabet. One night, as Josefa was writing a letter to her husband, the young Ferdinand surprised her by asking what she had told Mariano about him. It turned out that Ferdinand had read his mother writing his name. For Josefa and many who witnessed Ferdinand grow up, these early displays of talent were signs of a great future to come for the young Ferdinand.

Sharpshooter and Topnotcher

A turning point in the life of the young Ferdinand was his involvement in the murder of his father’s political rival Julio Nandalusan in 1935. At only 18 years old and still a university student, Ferdinand was found guilty of gunning down Nandalusan.

In the elections of September 1935, Julio Nandalusan bested rival Mariano Marcos for the position of district representative. To celebrate Nandalusan’s victory, his supporters organized a parade that went through the different municipalities of Ilocos Norte and passed in front of the house of the Marcoses. One of the trucks in the parade was fashioned to look like a hearse carrying the coffin of Mariano Marcos, a blatant taunt against the defeated candidate. The parade was said to have been embarrassing and deeply upsetting for Mariano. However, Nandalusan was never able to take on his position as district representative for only a few days after, he was shot dead with a single bullet in his house in Batac.

The investigation on Nandalusan’s murder pointed to the involvement of Mariano Marcos, his brother Pio Marcos, the young Ferdinand Marcos, and Quirino Lizardo. Evidence against Lizardo and the Marcoses was strong. Evidence pointed to Ferdinand’s direct involvement. The rifle used in the murder of Nandalusan belonged to the UP rifle team captain Teodoro Kalaw Jr., and among the accused, only Ferdinand had access to the UP ROTC armory where the rifle was kept. As such, Ferdinand was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Following his arrest, Ferdinand sought for an appeal with the intent of defending himself. In the meantime, he also began studying for the bar exam, and despite being imprisoned, Ferdinand managed to top the bar exam that year. With the bar topnotcher set to defend himself in court, the Marcos murder case was publicized and followed by many.

Though the public largely doubted any chance of Ferdinand’s acquittal, Ferdinand won the interest of Jose P. Laurel, then an up and coming jurist handling the case. Laurel, like Ferdinand, had also been found guilty of homicide, but was later acquitted due to his promise as a young man. Perhaps seeing the potential of the young Ferdinand, Laurel pleaded for the acquittal of Ferdinand and succeeded. Thus, the Supreme Court granted Ferdinand his freedom.

Despite Ferdinand’s involvement in Nandalusan’s murder, he went on to see a successful career in politics after working as a trial lawyer. Ferdinand first ran for office as representative to his district in 1949 and served three consecutive terms until 1959. He then won a seat in Senate in the 1959 elections and became the Senate minority floor leader in 1960. Up until 1965, Ferdinand served as the Senate President before finally running for the office of the President.

A War on Honors

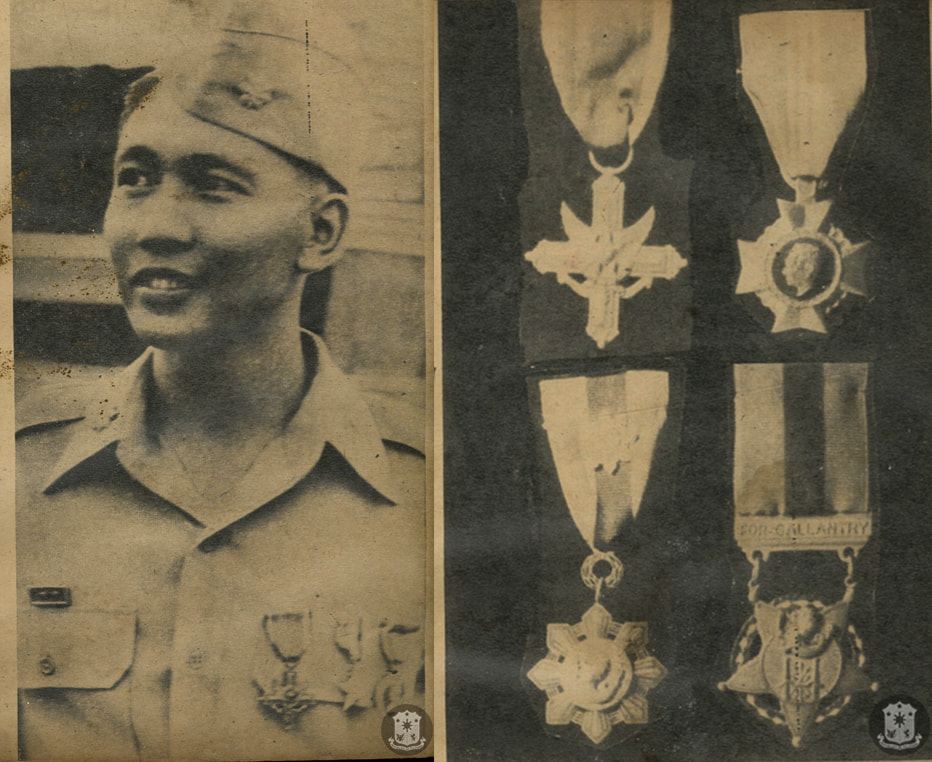

Ferdinand’s political success owed much to his eloquence and his prior military achievements. Following the outbreak of World War II, Ferdinand enlisted in the army and rose to the rank of major under the 14th infantry of the United States Army Forces in the Philippines – Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL).

Many of his biographies highlight his role in the defense of Bataan and in leading the guerilla group Ang Mga Maharlika; in 1962, Ferdinand claimed to be the “most decorated war hero of the Philippines”, supposedly receiving the US medals Silver Star, Order of the Purple Heart, and Distinguished Service Cross, pinned by Gen. Douglas MacArthur himself. Ferdinand’s exploits during the war are even dramatized in the film Iginuhit ng Tadhana, released merely months before the 1965 presidential elections.

Though it is true that Ferdinand fought during the Second World War, claims about his military prestige have long been disputed and disproven. As early as 1965, critics such as Nick Joaquin and Sergio Osmeña Jr. have been quick to point out the lack of evidence to back Ferdinand’s claims. As a recent study by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines shows, official wartime documents and works on Bataan make no mention of Ferdinand’s exploits, his receipt of the three US medals, or the existence of the Ang Mga Maharlika guerilla unit. In one instance when asked to produce evidence for Marcos’s honors, the government simply claimed that the establishing documents had been lost in a fire.

Official documents recording the correspondence between Ferdinand and various U.S. military officials show that, on multiple occasions, the US government did not recognize Ang Mga Maharlika as a guerilla unit due to the lack of evidence and inconsistencies in Ferdinand’s claims about their wartime accomplishments. Similarly, the official websites of the US medals make no mention of Ferdinand, and Ferdinand received 26 of his wartime medals from the Philippine army in 1962—21 full years after the war—on the basis of falsified war records. Furthermore, though Ferdinand later claimed to have reached the rank of lieutenant colonel, official US records make no mention of his promotion and instead recognize him as merely a major.

References

- Ferdinand Edralin Marcos. Senate of the Philippines. Retrieved from this site.

- Mijares, P. (1976). The conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. New York: Union Square Publications.

- National Historical Commission of the Philippines. (2016). Why Ferdinand Marcos should not be buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. Retrieved from this site.

- Nituda, V. (1979). The young Marcos. Quezon City: Foresight International.

- Scott, A. (1986, March 17). US auditors to examine documents related to Philippines’ alleged diverted funds. United Press International.

- Sharkey, J. (1983, December 13). The Marcos Mystery: Did the Philippine Leader Really Win the US Medals for Valor? He Exploits Honors He May Not Have Earned. The Washington Post.