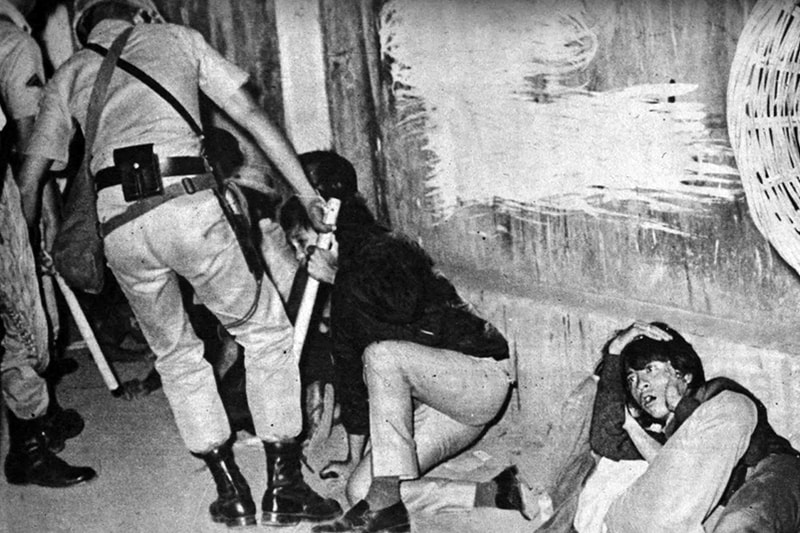

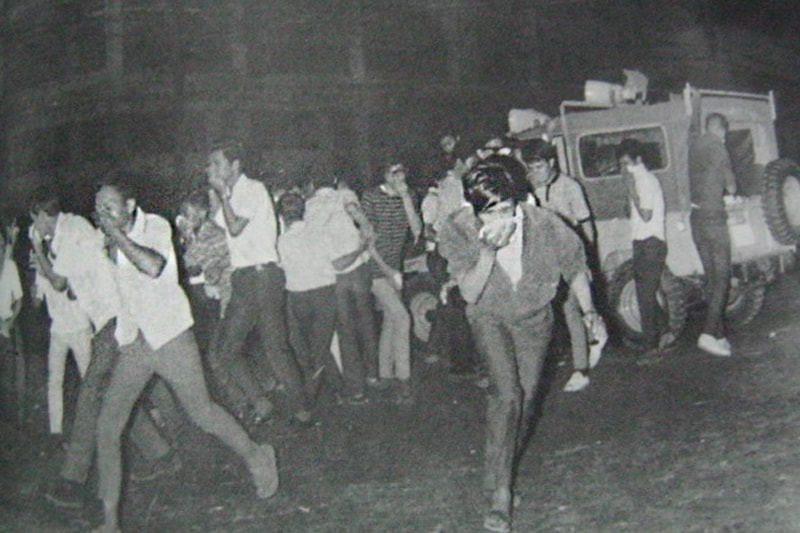

We look back at events before the declaration of Martial Law in 1972 that, in retrospect, could have served as signs of the impending dictatorship.

OPLAN MERDEKA

AUGUST 1967 – MARCH 1968

There is still some debate on whether classified military operation Oplan Merdeka, whose supposed goal was the secession of Sabah from Malaysia, really happened at all. Operation Plan Merdeka, a classified operation under the Philippine Constabulary, began with the recruitment of Tausug and Sama Muslims in Sulu. These peoples’ close cultural and commercial ties with Sabah meant that they could infiltrate the island without causing any alarm. The special commando unit that would infiltrate the disputed area was to be called Jabidah; they would convince the Sabah residents—without force—to secede.

The Constabulary is said to have promised the recruits a Php 50 monthly pay and admission to an elite unit of the armed forces; they got none of these after their secretive training on Corregidor Island. The recruits’ demands for pay and decent food and lodging, as well as their reluctance to carry out the operation on Sabah with force, is believed to have caused the massacre. In what is now known as the Jabidah Massacre, around 60 Moro trainees were allegedly killed by government troops. Their bodies? Burned and thrown into Manila Bay later on.

News of the killing of Moros in an isolated island in Luzon—whether fact or fiction—added fuel to the burgeoning Muslim separatist movement, a brewing rebellion that would legally justify Martial Law.