The Second ABS-CBN Shutdown

“Only after imposing authoritarian rule could President Ferdinand Marcos engage in the plunder of the Philippines’ resources on a much larger scale.”

– Nathan Quimpo, The Politics of Change in the Philippines

On May 5, 2020 ABS-CBN signed off the air after airing its primetime news program, TV Patrol. ABS-CBN, the country’s largest broadcast media, was ordered to cease its operations by the National Telecommunications Commission under threat of prosecution by the Solicitor General, Jose Calida. Ironically, the order came just two days after the world commemorated World Press Freedom Day. That the closure order came while the country was under quarantine restrictions and focused exclusively on the pandemic was met by criticism not only from a broad section civil society but even from members of Congress.[1] As of this writing however, the grant of even a temporary franchise remains doubtful.

Those who lived during the martial law years would know that this is not the first time the giant network suffered such fate. After 48 years, it is like déjà vu all over again. At that time though, all forms of free media were closed upon the declaration of martial law. Except that ABS-CBN had been at the receiving end of government regulators since the Lopez family established the network since the 1960s. As history would show, ABS-CBN, and the Lopez family, had weathered many storms, only to survive and face another one.

The 1972 shutdown

To understand the significance of the event, it is necessary to historicize and contextualize within the broader framework of pre-martial law politics and the relationship between the Lopez family and Ferdinand Marcos that started from amity and ended in enmity. The 1972 ABS-CBN shutdown, after all, was a sideshow to the larger events taking place around it.

Originally, the Lopez family amassed their wealth from large landholdings in Negros Island planted with sugar. The so-called sugar barons, because of their immense wealth, became a strong lobby group within the corridors of power and greatly influenced both domestic and foreign economic policies. Capturing elective positions, therefore, became a natural consequence of this economic power, at the local level first and then at the national level. The Lopez family’s fourth generation, led by the brothers Eugenio and Fernando, epitomized this so-called `one-two punch’ enterprise – while Eugenio took care of the business side of the family’s business, Fernando entered national politics to corner contracts and business opportunities as well as to protect the enterprise from unwanted threats and challenges.

Likewise, the brothers diversified their business to avoid the vicissitudes of the sugar industry – fluctuating prices in the world market and occasional labor problems. This strategy, later to be adopted by other landlords, would eventually produce what is perhaps the country’s first conglomerate. However, their investments into the transportation industry yielded results that were quite ruinous for the family. The first of these ventures was Panay Autobus. By the late 1930s, the family invested in an industry that was both pioneering and promising – aviation. Starting out as an aerial taxi company like Philippine Airlines, the Iloilo-Negros Aerial Taxi Company (INAEC) was created firstly to transport sugar barons to and from Manila. Later on, the company expanded into scheduled services between Manila and other major urban centers. Eventually, INAEC metamorphosed into a full-fledged airline, the Far East Air Transport Inc. (FEATI), providing links to Asian cities such as Hong Kong and Shanghai. The Pacific War, however, ended this enterprise abruptly when its planes were destroyed by Japanese forces. FEATI was resurrected right after the war, with an even bigger fleet than Philippine Air Lines’ and an airfield (Grace Park in Caloocan) exclusively for its operations. But a series of crashes attracted attention that led to a congressional investigation focusing on their safety record. Had the Roxas administration been friendly to the Lopezes, the company would have earned a reprieve. But because they were on the wrong side of the political fence by supporting the losing candidate (Osmena) in the 1946 presidential elections, the full might of the government’s regulatory powers was brought to bear. So that in the end, the Lopez family was pressured to sell FEATI’s assets to PAL, whose owner, Don Andres Soriano, was a Roxas supporter. This event may have instilled the irrefutable value of proximity with the chief executive.

By the late 50s and early 60s, the Lopez brothers were able to make a rebound, thanks in large part to their friendly relations with President Garcia. In 1957, Eugenio Lopez bought Alto Broadcasting System (ABS) from Antonio Quirino and merged with Chronicle Broadcasting Network (CBN) they had brought earlier.[2] The big break tough came in 1961 with their purchase of MERALCO, an American power firm.[3] But because Diosdado Macapagal won an upset electoral victory over Garcia a few months later, the fate of both companies would be imperiled again by the rough and tumble world of Philippine politics.

For the next few years, the Lopez conglomerate faced charges of franchise violations and even suspensions that the 1969 presidential elections proved an attractive option as a way out. The family was faced with a dilemma – whether to ask Fernando to run for the presidency or to ally with a popular politician who was more likely to win the next election. They chose the latter, a decision that would eventually lead to their downfall.

With Fernando running as vice to Marcos, Eugenio gave full support to the Nacionalista party standard-bearer. The first six years of the Marcos-Lopez partnership, from 1965 to 1971, may be characterized as cordial. From then on, however, things came to a head. Lopez attacked Marcos and Imelda in media while the president countered by attacking Lopez and their ilk as “oligarchs.” It did not help that Eugenio threw a lavish party on the occasion of he and his wife’s fortieth wedding anniversary, so opulent and ostentatious that it did not escape notice of both Marcos and activists. In the end, however, it was Marcos who sued for peace by paying Eugenio a visit at his MERALCO headquarters, patching up the feud temporarily for Marcos would come with a vengeance for the next round (McCoy 1994, 508).

In the early morning of September 23, 1972, then Lt. Rolando Abadilla went to the Broadcast Center along Bohol Ave. in Quezon City to take over ABS-CBN. Earlier, the Lopez-owned Manila Chronicle, like all broadsheets, were padlocked. Like a fallen prey, two cronies immediately devoured the downed media giant. Kokoy Romualdez, Imelda’s favorite brother, took over the facilities of Manila Chronicle and came up with his own paper, The Daily Express[4]. Sugar king Roberto S. Benedicto took many of the television station’s equipment and came up with his own channel – Kanlaon Broadcasting Company (Channel 9). When a fire destroyed the KBS center the following year, they moved to the Broadcast Center and took over the entire building and all its equipment, known to ABS-CBN employees as Looter’s Day. Benedicto likewise used ABS-CBN’s channel (Channel 2) to form a new TV station – Banahaw Broadcasting Corporation (or BBC)[5]. Never was the Lopez family compensated for the takeover. To the contrary, in October 1979 the Lopez family was ordered to pay the government millions of pesos for tax arrears and fines. (McCoy 1994, 509).

The prize jewel though in the Lopez empire was MERALCO. Because it was a publicly-listed company with hundreds of shareholders, a different approach was hatched. Eugenio Jr. (Geny) was arrested on the pretext that he was involved in a plan to assassinate the president. Marcos used this as bait for Eugenio to sign a document relinquishing control of the power firm. In exile in San Francisco and close to death, Eugenio signed but with a condition, for the regime to release Geny so he could see his son for the last time. Marcos did not keep his part of the bargain and thus refused the dying man’s wish. Undeterred, the Lopez family successfully executed an escape plan the following year for Geny and his co-accused, Sergio Osmena III (Serge), from their detention in Fort Bonifacio. Both ended up seeking asylum in the US where they became active in the anti-Marcos campaign.

In the aftermath of the 1986 People Power Revolt, an opportunity came for Geny to regain their properties. As part of the democratic government’s program of recovering sequestering ill-gotten wealth from Marcos and his cronies, the government sequestered corporations including ABS-CBN, Manila Chronicle, and Meralco. As can be expected, he found a sympathetic president in Cory Aquino for both suffered terribly under the Marcos regime. As many martial law activists became part of the government or ran for elective office in Congress and Senate, Geny found a sympathetic power base by which to wrest control of ABS-CBN, including the Manila Chronicle and MERALCO. Like Lazarus, ABS-CBN came back from the grave, resurrected once again after fourteen years. After only a few years in operation, ABS-CBN reached the top of the charts and regained their premarital law standing.

Bringing the (predatory) state back in?

Patron-client relations and rent-seeking perspectives offer convincing explanatory power when looking at the Lopez family’s fortunes until the advent of martial law. One may even argue that this relationship with the state persisted after 1986. ABS-CBN lent its support to the hastily-assembled Ramos presidential run in 1992 and assigned one of its top executives, Rod Reyes, to handle the media campaign. The gesture paid off when Reyes was appointed Press Secretary during the Ramos administration. And when media became critical of Estrada’s errant governance, media outfits became the new targets of the populist president. The Gokongwei-owned Manila Times was summoned to court for a libel case and threatened with closure, a grim scenario that forced management to sell the paper to Estrada crony Dante Ang[6]. The Philippine Daily Inquirer almost suffered the same fate when the irate president asked his friends in business to withdraw their advertisements in the country’s number one newspaper. Interestingly, ABS-CBN enjoyed being on the opposite side of the fence because one of the Lopez scions married a presidential daughter. The same may be said in the following administration when one of its most visible broadcasters became Vice President. Perhaps it is not wrong to say that the same cordial relations existed during yet another Aquino presidency. But then, like boom and bust cycles, the Lopez family may be in for rough times. Even when the charismatic Gina Lopez became Environment Secretary in Duterte’s Cabinet, her advocacy to ban mining operations did not sit well with many of the president’s supporters. Furthermore, the Lopez family’s interests in power generation only made this advocacy more untenable. In spite of her wide popularity among a cross section of society, Duterte caved into the powerful mining lobby to take her out of the Cabinet.

How do we then make sense of this second shutdown? Current discourses on the current president had centered on populism as well as on its rabid manifestations – Dutertismo[7]. Shifting the discourse back on the nature of the Philippine state may be more useful at this point. A departure from this discourse is a recent article which framed Duterte as the leader who had the gumption to take on the powerful oligarchs who, historically, have plundered state coffers to their advantage. In so doing, the article suggests, Duterte did what his predecessors could not, that is to stand up to mighty oligarchic class under the Philippine state had been powerless to control (Heydarian 2020). But while Duterte may have stood up against oligarchs in the past, the pandemic had shown his vacillating position towards them[8].

And here, Evans and Skocpol’s work[9], and its catchy title, may give us a lead on where to train our sights. At the time when Bringing the State Back In was published, many of the scholarship on development focused on non-state actors – among them social movements, radical politics, and democratization. At the same time, the so-called East Asian miracle economies gained attention in academic circles, focusing on the role of the state in economic development. More importantly, succeeding scholars who toiled in this genre provided us a typology of states (strong/weak, developmental/patrimonial, etc.) and comparative studies to differentiate and illustrate outcomes.

Simply put, predatory regimes are both extractive and coercive, both qualities that complement each other. As democratization scholar Larry Diamond (1998, 17) explains further:

“Corruption is the core phenomenon of the predatory state. It is the principal means by which state officials extract wealth from society, deter productive activity and thereby reproduces poverty and dependency… Patrons distribute the crumbs of corruption to maintain their clientelist support groups. Corruption is to the predatory state what blood supply is to a malignant tumor.”

In its original formulation, predatory states however referred not to the Philippines but to elite government bureaucrats preying on business such as what may be found in Indonesia. The Philippine problematic however has produced variations. For example, Hutchcroft (2000) would remind us of the phenomenon of patrimonial oligarchy or a more direct term, predatory oligarchy:

“the Philippine state is more often plundered than the plunderer; we find not a predatory state but a predatory oligarchy. The primary direction of rent extraction is not toward a bureaucratic elite based inside the state but rather toward oligarchic forces with a firm independent base outside the state.”

In another exposition, Quimpo (2010) avers that what we have is a predatory regime. As differentiated from a clientelist regime, Quimpo describes predatory regimes as:

“A clientelist regime is one based on networks of dyadic alliances involving the exchange of favors between politicians and their supporters – material gains for political support … Under a predatory regime, the checks are breached and overwhelmed. Clientelism and patronage give way to pervasive corruption, a systematic plunder of government resources and the rapid erosion of public institutions into tools for predation.” (p.50)

Thus, while Hutchcroft puts forward the thesis on oligarchic plunder, Quimpo enriches this concept with the proposition that such plunder could be made more efficient and far-reaching under an authoritarian president.

Looking back, the takeover of the Lopez empire was but the prominent example of this setup. The Jacinto family suffered the same fate as a consequence of their support for Sergio Osmena, Jr. in the 1969 presidential election. The government took over Jacinto’s steelmaking companies, including the biggest, Iligan Integrated Steel Mills, on the pretext that it was unable to repay its foreign debts. The owner, however, revealed that the government reneged on the loan arrangement and that Marcos demanded a two-thirds share in the company. A similar fate awaited the owner of Volkswagen Philippines. Having complied with all government regulations in the nascent car industry, the government tilted the rules in favor of the Silverios, owner of Delta Motors, Toyota’s sole agent in the country, and supplier to the Armed Forces, driving the company to close shop (Rivera 1994, 84-5). Herminio Disini benefitted from the same tactic when the government slapped a 100% tax on cigarette filters to all tobacco manufacturers. However, the government later issued Disini a 90% exemption, making him the sole supplier of the commodity. In the end, it was only by employing the full coercive powers of the state and dismantling opposition such as courts and free media was Marcos able to destroy the old oligarchy. But this did not translate to a state insulated from predation and capable of instituting reforms. In its stead, a new crop of more vicious oligarchs (cronies) came to the fore – Roberto Benedicto, Danding Cojuangco, Herminio Disini, Lucio Tan, Rodolfo Cuenco and many others.

This trend continues as we look at the regime’s favorite businessman, Davao-based businessman Dennis Uy. Benefitting from the state’s allocation of resources to its allies as well as denial to opponents or rivals, Dennis Uy has expanded his business enterprise exponentially. Since 2016, Uy had ventured into a host of business enterprises such as oil, water, and power utilities, shipping, real estate, food retail, gambling, and telecommunications totaling 36 companies overall (Rivas 2019). From 11 companies in 2016, Uy had amassed 19 companies after only three years into the Duterte presidency. Aimed at breaking the `oligarchic’ duopoly of Smart and Globe, he was awarded the third telecommunications franchise even when he had no experience in the industry and had to partner with Chinese experts to rationalize the award. Furthermore, Uy’s access to local banking capital enabled him to gobble up industries notwithstanding his company’s audit record. Indeed, access to state resources is key private accumulation. As to whether loan guarantees were extended to Uy or a bailout in case of a default will only add to the burgeoning woes and frustration to the public already battered by the pandemic.

As the country slowly emerges from quarantine restrictions, media can now shift its attention to news items that were previously drowned out by the pandemic, among them overpriced procurement transactions entered into by government officials. The state of emergency has been an excuse to stifle human rights and to enter into shady deals without the restrictions of oversight procedures. Thus, it is not surprising if some LGUs insist on restrictive quarantine measures even if health records show otherwise. By shutting down ABS-CBN, the government had sent a strong signal to other media outfits of what fate may befall them if they fail to tow the line.

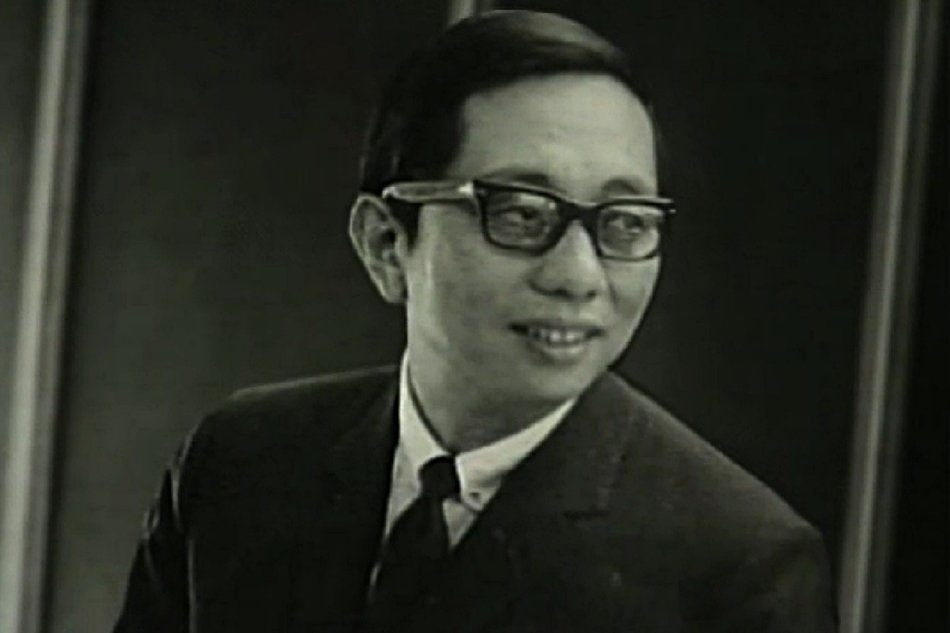

Header image from ABS-CBN News article Bomb threats & dinners at the Palace: Geny Lopez and the last hours before Martial Law.

References

- See for example “Speaker: SolGen, NTC Face Day of Reckoning,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 9 May 2020, 1. See also “Campuses React to ABS-CBN shutdown,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 9 May 2020, C1-C2.

- <https://www.abs-cbn.com/who-we-are/our-story>. Accessed May 12, 2020.

- Manila Electric Railways and Light Company (MERALCO) was established in 1903 by Charles Swift, engaged in power generation and distribution and in operating the electric rail (tranvia) system in Manila.

- Jokingly referred to as the Daily Suppress by the opposition.

- BBC also stood for its catchy meaning and theme song Big, Beautiful Country composed by another sugar baron, Jose Mari Chan.

- https://ifex.org/philippine-press-threatened-by-manila-times-precedent/. Accessed 15 March 2020.

- See for example Curato, Nicole. (2017) “Flirting with Authoritarian Tendencies?: Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism,”Journal of Contemporary Asia, 47(1), 142-153. DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751; Nagano, Yoshiko (2018) Understaning the Rise of Dutertismo in the Philippines: With the background of its economic growth for the past ten years. Conference Paper. Fourth Philippine Studies Conference in Japan (PSCJ), Hiroshima University and, Parreno, Earl G. (2019). Beyond Will and Power: A Biography of President Roa Duterte,Manila: Optima Typographics, 2019.

- Take for example his praises for Ramon S. Ang’s San Miguel Corp. whose donation to the fight against the coronavirus totaled more than a billion pesos. And in a rare act of contrition, a humbled Duterte apologized to the Zobel brothers and Manny Pangilinan for the hurtful words he had thrown at them in the past during his address to the public held May 4, 2020.

- Evans Peter B., Dietrich Reuschmeyer and Theda Skocpol. (Eds.) Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press.

Works consulted

- Aquino, Belinda. (1987). Politics of Plunder: The Philippines Under Marcos. Quezon City: University of the Philippines College of Public Administration.

- Bello, Walden. (2019). Counterrevolution: The Global Rise of the Far Right. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Committee to Protect Journalists. (1999 April 13) Philippine press threatened by “Manila Times” precedent. <https://ifex.org/philippine-press-threatened-by-manila-times-precedent/>.

- Diamond, Larry. 1998. Developing Democracy: Towards Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Heydarian, Richard. (2020 May 12) “The Fourth Republic: Duterte vs. oligarchs,” Philippine Daily Inquirer. <https://opinion.inquirer.net/129721/the-fourth-republic-duterte-vs-oligarchs>

- Hutchcroft, Paul D. (2000). Booty Capitalism: The Politics of Banking in the Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- McCoy, Alfred W. (1994) “Rent-Seeking Families and the Philippine State: A History of the Lopez Family. In McCoy A.W. (ed.) An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines, 429-536, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Mendoza, Meynardo P. (2013) “Binding the Islands: Air Transport and State-Capacity Building in the Philippines, 1946 – 1964,” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, 61 (1), 77-104, (January).

- Quimpo, Nathan Gilbert. 2010. “The presidency, political parties and predatory politics in the Philippines.” In Yuko Kasuya and Nathan Gilbert Quimpo, (eds.) The Politics of Change in the Philippines, 47-72, Manila: Anvil.

- Rivas, Ralf. Dennis Uy’s Growing Empire and Debt, Rappler, January 3, 2019. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/219039-dennis-uy-growing-business-empire-debt-year-opener-2019?fbclid=IwAR3mrEpnUADcu-WcqzQHtFmvqlXk1SFvPGS3d6Mtr1B7fF2foLLBdBGLZss

- Rivera, Temario C. (1994) “The State and Industrial Transformation: Comparative and Local Insights.” Kasarinlan: A Philippine Quarterly of Third World Studies, 10(1), 55-80.

- Romero, Segundo E. (2020 May 11) “Duterte’s feel-good moment,” Philippine Daily Inquirer. A7.