Reading Martial Law in Children’s Literature

Much of the difficulty in teaching Martial Law to younger children comes from a fear of its political baggage. After all, how does one explain difficult topics such as the abuses of the Marcos dictatorship in a manner suitable for children without undermining the importance of knowing that these injustices happened? Without an awareness for either, what we hope to convey may end up becoming muddled and altogether lost.

This concern for teaching children about the difficulties of life in an appropriate manner has formed the crux of children’s literature that deal with sensitive topics. Yet, despite the difficulty of striking this balance, numerous authors have written books that explore Martial Law without compromising its grimmer realities.

In this exhibit, we look at the ways in which three children’s books explore how Martial Law affected the lives of children. In looking closely at how fiction depicts Martial Law, we gain a better idea of how authors frame Martial Law for children and what lessons we can hope to gain from framing Martial Law in these ways. More importantly, we also hope to understand why works that discuss the grim realities of history remain important for a readership too young to have experienced them.

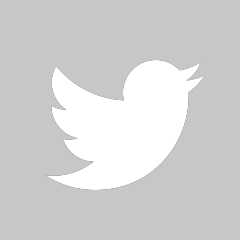

Isang Harding Papel

Publisher: Adarna House | Language: Filipino (Tagalog) | Age Recommendation: 8+ | available at adarna.com.ph

This book by Augie Rivera looks at the relationship of 7-year-old Jenny with her mother Chit, an actor incarcerated for staging anti-Marcos street performances. As a result of her mother’s imprisonment, Jenny grows up separated from her mother whom she visits only once a week.

Throughout the book, we see how Jenny is affected by her mother’s imprisonment. On the one hand, Jenny copes by keeping track of all her stories to share for when she visits her mother on Sundays. She also finds company in the children of other inmates and most importantly, in her maternal grandmother Lola Priming. In turn, Chit does her best to comfort Jenny: every time Jenny visits, Chit gives her a paper flower she made herself.

On the other hand, Chit’s absence cannot be ignored. Inasmuch as Jenny tries to adapt, she cannot help but feel heartbroken by how her mother misses the milestones of her life and how her situation earns her the teasing of other children. Her mother’s absence is made even more pronounced as she accumulates the paper flowers to the point that they resemble a garden; though meant to comfort her, the artificial flowers cannot substitute for her mother’s presence.

The story’s power lies in how it subtly critiques common assumptions about Martial Law. Martial Law is first introduced through the knowledge of Lola Priming who says the cleanliness, order, and peace of Martial Law are part of Marcos’ vision of a progressive New Society. The book even quotes Marcos’ campaign slogan: “Para sa ikauunland ng bayan, disiplina ang kailangan.”

This picture of Martial Law as peace and order, however, is immediately juxtaposed with Jenny’s family situation. As the book blurb puts it: “Panahon ng Martial Law, panahon ng pinaiiral na disiplina para daw [sic] sa kaunlaran. Pero para kay Jenny, panahon iyon ng pagkakalayo nilang mag-ina.” This critique is made even more pointed when we consider the reason for Chit’s imprisonment. Though it is told as a joke, Rivera gives a glimpse into the authoritarian nature of the Marcos presidency when Chit explains that her imprisonment may have solely been because her street plays angered the President.

In effect, Rivera points our attention to another kind of artificiality in the story: the idyll of Martial Law. As Chit’s situation reveals, the peace and order of Martial Law rest on the suppression of democratic principles. Thus, the supposed peace of Martial Law is merely a facade that masks its darker truths. The picture book implores us to ask: At what cost is discipline being enforced by the Marcos regime? Who benefits and who in turn suffers?

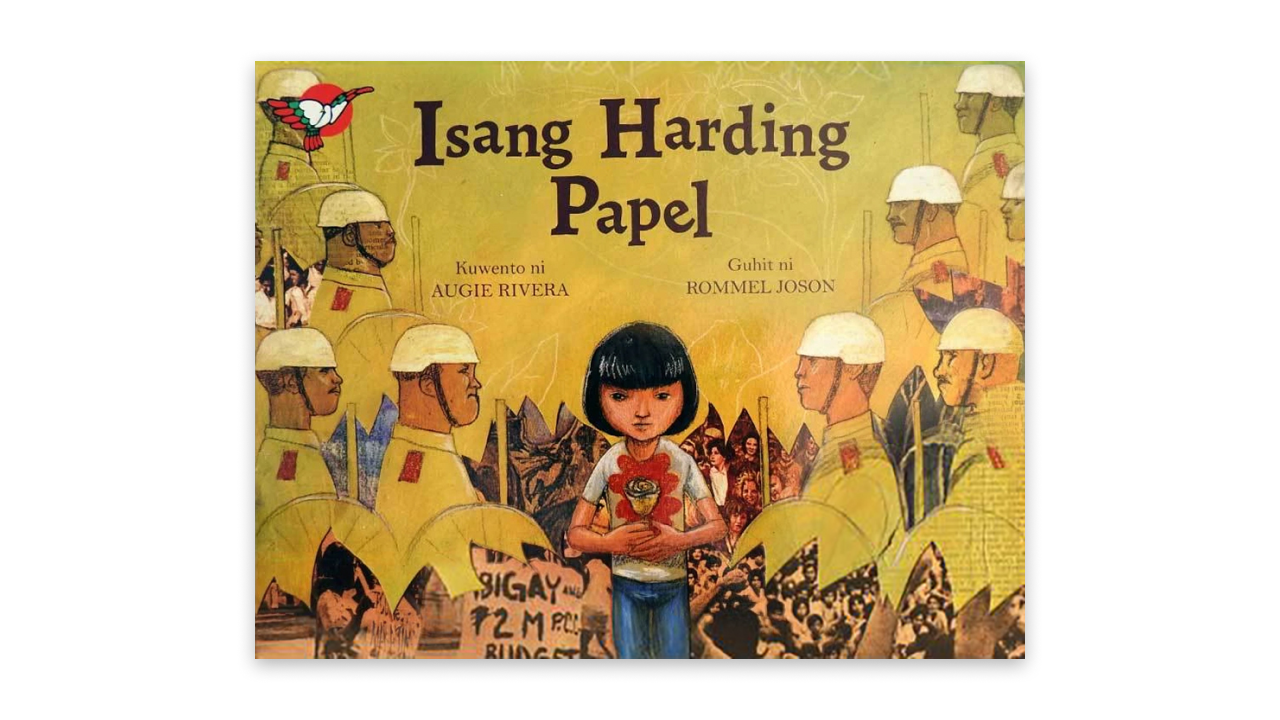

Si Jhun-Jhun, Noong Bago Ideklara ang Batas Militar

Publisher: Adarna House | Language: Filipino (Tagalog) with English translation | Age Recommendation: 10+ | available at adarna.com.ph

As opposed to Isang Harding Papel, Rivera’s other book on Martial Law Si Jhun-Jhun, Noong Bago Ideklara ang Batas Militar is more explicit in its approach. The book introduces Jhun-Jhun, a young boy frustrated by the sudden change in his older brother Jaime’s behavior. Determined to find out why Jhun-Jhun follows his brother to work but in the process, suddenly finds himself in the middle of a violent clash between anti-Marcos protesters and Metrocom agents during the First Quarter Storm.

Rivera’s narration and Vallesteros’ illustrations do not shy away from depicting the political and violent clash between protesters and Metrocom agents. Protesters are drawn holding up signs that read “FM ‘BUSOG’ SA PERA NG BAYAN,” and make direct references to the US involvement in the Marcos dictatorship; meanwhile, Rivera describes how the Metrocom agents use guns and smoke bombs to disperse the rally.

Beyond its depiction of violence and protest, however, the book is also radical because it touches on another reality children had to face during Martial Law: the forced disappearances of family members. Jaime is one of the many protesters seized after the rally, and his forced disappearance deeply scars Jhun-Jhun. The family’s failed attempts to locate Jaime only dishearten Jhun-Jhun to the point that he blames himself for his brother’s disappearance.

What is significant about Rivera’s approach here is its exploration of how the Marcos dictatorship affected Filipinos on both a macro and micro level. There are the protesting workers who undoubtedly feel the effects of Marcos’ corruption in the economic sphere, but there is also Jhun-Jhun who must deal with his strained relationship with Jaime and later with Jaime’s forced disappearance—all in part because of the Marcos dictatorship. This kind of approach leads us to an understanding that Martial Law was more than just a series of events that happened in the past, but rather a tumultuous experience that continues to affect the everyday lives of many families even today.

Jhun-Jhun’s experience, however, does not stop at trauma. Over time, he learns to deal with his brother’s loss, and it soon becomes a kind of political awakening. At the end of the book, Jhun-Jhun follows in his brother’s footsteps and joins in protesting the Marcos dictatorship. Though Rivera pushes the idea to the extreme in having Jhun-Jhun protest, this highlights yet another aspect of children’s literature on Martial Law: its emphasis on the relationship between children and politics. Rivera demonstrates that children are very much a part of those affected by political events, and that, though they do not necessarily need to take to the streets to do so, children have something to contribute to the ongoing fight for what is right.

Salingkit: a 1986 Diary

Publisher: Anvil Publishing | Language: English | available as an ebook in multiple platforms

Cyan Abad-Jugo’s Salingkit: a 1986 Diary stands out as one of the few young adult novels that deals with Martial Law. However, unlike the previous books, Abad-Jugo’s novel takes place in the year 1986, the year of the EDSA Revolution and the Philippines’ transition from a dictatorship to a democracy.

The novel is centered on 14-year-old Kitty Eugenio, who is left in the care of her extended family as her mother seeks a job in America. As a result, Kitty must negotiate with the sudden changes in her life vis-à-vis the changing times. Inasmuch as Kitty wishes to remain in her bubble of New Wave music appreciation, her encounters with her extended family and peers lead to her to come face-to-face with the country’s changing political landscape.

For most of the novel, Kitty is a passive observer of the country’s changes. Though Kitty is anti-Marcos in political stance, this sentiment stems mostly from the influence of her family—especially of her older cousin Alan; beyond that, however, Kitty shows little concern for the country’s political situation. It isn’t until she becomes involved with Bensy Salcedo, the son of a Marcos crony, that she begins to interrogate her assumptions about politics, such as the popularized Marcos-Cory dichotomy and more importantly her political beliefs independent of others.

In many ways, Kitty’s journey into adolescence is meant to mirror the turmoil the country experienced in the months following the fall of the Marcos dictatorship. Like the many who experienced the transition to democracy, Kitty is forced to make sense of a fractured political landscape: from the resistance of the Marcos loyalists to the shortcomings of the Aquino administration brought about by infighting and its failure to resolve issues from Martial Law. In the process, Kitty comes to understand that one cannot comprehend the political situation as merely black-or-white. At the same time, Kitty also learns that in times like this one cannot remain apolitical in a post-EDSA democracy rife with conflict:

Kuya Alan always seems to have a cause to believe in. I wonder if maybe I should have joined [the Animal Welfare League] even if Dominique and Wanda joined too. I hate to say this, but maybe even the [Marcos] Loyalists have some cause they believe in. . . .

So what do I believe in?

Kitty’s adjustment to the post-EDSA life is further complicated by the glaring absence of her father who disappeared two years before EDSA. In various diary entries, Kitty writes about her fear that, in the wake of Martial Law’s end, many of those who fought the dictatorship—her family included—have already begun to move on and forget those who disappeared. And her reluctance to share these points to her belief that such concerns remain marginal to the larger picture of the country’s return to democracy.

This emotional struggle plays into the novel’s much larger theme of examining the post-EDSA democracy. While there was cause to celebrate the EDSA Revolution, many of its promises remained unfulfilled in the years that followed; those who abused their power have yet to pay for their crimes, while those who suffered have yet to receive reparation. Kitty’s own situation captures how there is still much to tread in healing the wounds left behind by Martial Law—even until today.