The first election

As many parts of the world remain in lockdown mode from the COVID-19 pandemic and as Catholics mark Holy Week, an almost forgotten event passed by without notice except for those who lived through it. Yet, this event is an important milestone in the history of martial law in the Philippines. For it had many firsts – the first major election of the martial law era; the first time we used the parliamentary system for the soon-to-be-opened legislature (matched by a new building in Quezon City) which Marcos abolished in 1972; and, the first and only that political forces of different persuasions worked together in an election.[1] We may also add that for a number of student activists, it was their first time to experience detention.

In January of 1978, Marcos called for an election scheduled for April 7 of that same year to fill the new legislative body called the Interim Batasang Pambansa (IBP). The election was partly to highlight the normalization process taking place in the country to the international community. Partly it was pressure from the Carter administration’s desire to return the country to the path of democratic rule. Jimmy Carter, the 39th US president, introduced human rights into US foreign policy objectives, a distant departure from the previous Republican presidents before and after his term. A motto among Washington policymakers at that time goes like this, “I don’t care if he is a `sonofabitch’ so long as he is our sonofabitch’!” As the Cold War rivalry turned into proxy wars in many parts of the world, the US-supported dictators who ruled with impunity and reckless abandon as they enjoyed full American support so long as they promote or preserve America’s interests.

Thus, Carter’s libertarian orientation reversed US foreign policy towards its authoritarian allies. In Asia, there were congressional hearings on widespread abuses made by the military in South Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines and how US aid abetted them. Likewise, a number of high-profile prisoners in the country were released. Thereafter, economic assistance and military aid were given only if recipient countries subscribed to a modicum of civil liberties and political reforms. It was in this context that the 1978 elections for members of the Interim Batasang Pambansa took shape.

At the outset, Sen. Jovito Salonga of the Liberal Party and other oppositionists did not believe that a fair and credible election would be possible under Marcos and instead opted for a boycott. Only former Senators Lorenzo Tanada, Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo, and the detained Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino took up the challenge.[2] The immediate task at hand was to form a political party and bring in oppositionists of various ideologies in so short. While Sen. Tanada could talk to the national democrats and Sen. Rodrigo with the social democrats, Ninoy brought in previous politicians. Thus, was born the LABAN (Lakas ng Bayan] coalition, the opposition party in Metro Manila.

LABAN poster for the April 7 Batasang Pambansa elections

LABAN’s slate included was an assortment of sorts. The national democrats fielded three candidates – former UP student leader and School of Economics teacher Fernando “Jerry” Barican, Zone One Tondo Organization (ZOTO) head Trinida “Trining” Herrera, and Alex Boncayao, a labor organizer from the Federation of Free Workers (FFW). The inclusion of so-called progressives such as the 1971 Constitutional Convention member Aquilino “Nene” Pimentel and former student leader Charito Planas were a welcome addition to the Manila-Rizal Party Committee of the CPP. Other members of the slate were civil libertarians and anti-Marcos politicians such as former senators Ramon Mitra and Francisco Rodrigo, former congressman Neptali Gonzales, former 1971 Constitutional Convention delegate Teofisto Guingona, journalists Alejandro Roces, Napoleon Rama and Ernesto Rondon, Aquino’s legal counsel Juan T. David and former Commission on Elections Chair Jaime Ferrer.

It was a David vs. Goliath struggle. Even if LABAN could not match the administration’s Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) party juggernaut in terms of resources and support, the election became a valued training exercise for organizing and conscientization especially the youth. After all, the election provided an opportunity to expose the systemic ills brought about by the Marcos regime and discuss this openly to the public. Many Ateneo students became actively involved in the campaign by printing and distributing election materials, organizing campaign meetings, doing house-to-house campaigns, training poll watchers, as well as acting as watchers themselves on the day of the election. A number wrote for LABAN’s periodical Malayang Pilipinas [Free Philippines].[3]

The climax of the campaign was the noise barrage in Metro Manila on April 6 the eve of the elections. As Sen. Nene Pimentel would later explain, the noise barrage was meant to demonstrate the people’s opposition to the regime even if their votes may not be counted. Catholic churches also participated by ringing its bells to signal the start of the protest. The organizers could not have anticipated its success as the boisterous expression of support for LABAN lasted well into the night. People banged pots and pans, sounded horns, and in some places put burned rubber tires. That the April 6, 1978 noise barrage was a spontaneous outburst of resentment and defiance did not escape Marcos’ attention.

Why LABAN lost all of its 21 candidates is often answered by the idea that Marcos would not tolerate any opposition to his rule. Perhaps. But the turnout in provincial areas, notably in Cebu, demonstrated that opposition candidates like Hilario Davide, Jr. and his teammates at the Pinaghuisa party were able to score victories. In a recently released memoir, Corazon C. Aquino recalled that the noise barrage of April 6, 1978, was so successful that the protest action shocked Marcos to the point that he ordered the COMELEC to shut out all the LABAN candidates in Metro Manila.[4]

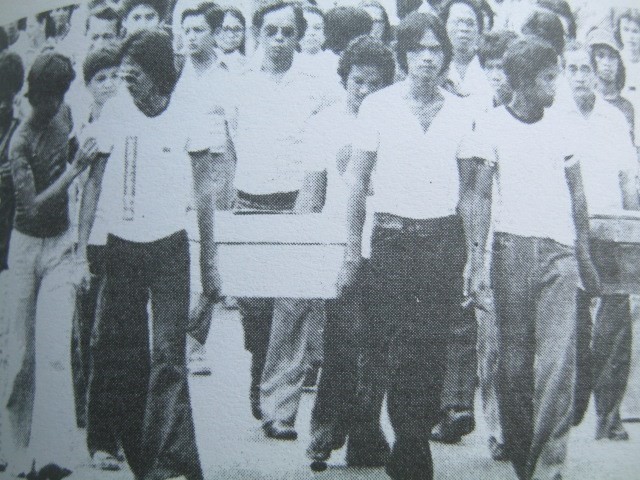

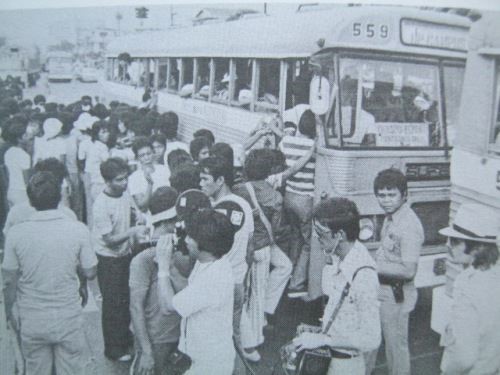

For many, the result was a foregone conclusion.[5] But not a few wondered why even obscure KBL candidates were able to dislodge even the popular Ninoy Aquino. The cheating was so brazen that LABAN called for a protest march for April 9. Activists from the Ateneo de Manila joined 600 other protesters. They march was to gather at the Welcome Rotunda at the Quezon City-Manila boundary and march all the way to the COMELEC office in Intramuros. But before they could enter Manila, they were stopped by METROCOM troops of the then Philippine Constabulary. The protesters were then hauled on government-owned and operated Metro Manila buses and brought to Camp Bagong Diwa in Bicutan, Taguig

The protest march as it approached Welcome Rotonda in Quezon City. Photo courtesy of Mr. Alan Alegre

Arrested protesters being hauled to Camp Bagong Diwa in Bicutan, Taguig in government-owned Metro Manila buses. Photo courtesy of Mr. Alan Alegre.

A defiant Sen. Lorenzo Tanada resisting his arrest and those of all the protesters while inside a police vehicle to be taken to Camp Bagong Diwa in Bicutan, Taguig. Photo taken from Aquilino Q. Pimentel’s book Martial Law in the Philippines: My Story, p.187

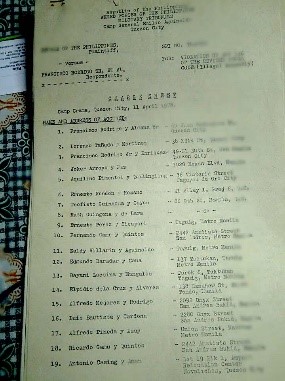

All demonstrators, from Senators Lorenzo Tanada and Soc Rodrigo, Tito Guingona, and Joker Arroyo down to the last member were charged with illegal assembly, illegal possession of deadly weapons, and subversive materials. Though scary and difficult at first, detention for the youth was made tolerable by the elders in the group as well as the “full-time residents” of Bagong Diwa who charged with graver offenses like rebellion. Accustomed to life in prison, they organized group games, singing sessions and other activities to while away the time. Students were also given tasks for the upkeep and maintenance of their living quarters. After a few days, Ateneo students were released through the intercession of University president Father Jose A. Cruz, S.J.[6] Students from other schools were likewise released on the same day. In the meantime, ring leaders like Nene Pimentel and Joker Arroyo would have to stay a little longer

A copy of the charge sheet filed against the protesters. Photo from the SELDA Papers, Special Collections, UP Diliman Library.

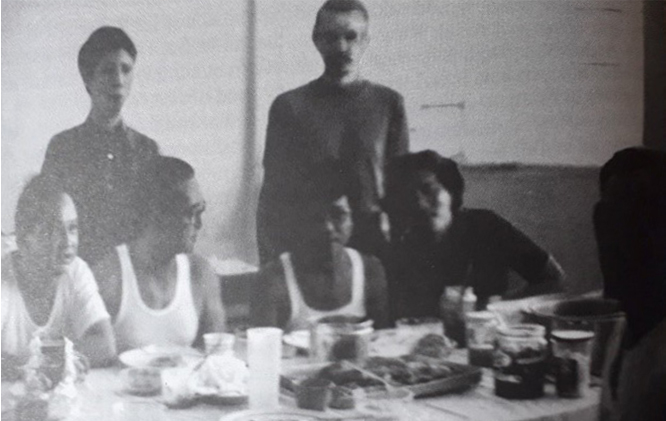

A souvenir photo of the alleged ring leaders of the April 9 protest march. From left; standing – Fr. Romeo J. “Archie” Intengan, Teofisto “Tito” Guingona; seated – Joker Arroyo, Sen. Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo, senatorial candidate Ernesto “Ernie” Rondon and fellow detainee Fidel Agcaoili (not a participant to the protest). Photo taken from Aquilino Q. Pimentel’s book Martial Law in the Philippines: My Story, p.192

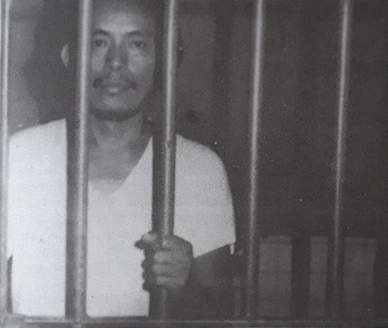

A young Nene Pimentel in jail for participating in the protest action of 9 April 1978. Photo taken from Aquilino Q. Pimentel’s book Martial Law in the Philippines: My Story, p.185

The eventful 1978 election had many repercussions. One is that it shattered the illusion that Marcos may still bargain with the opposition and offer concessions. This event made clear to everyone that elections as a means to effect political change is no longer feasible. From then on, oppositionists would try their hand on an armed struggle with the formation of the Light-A-Fire Movement and the April 6 Liberation Movement. Some linked up with the Moro National Liberation Front in search of training and hardware.

More importantly, the event solidified non-communist opposition to martial law. Because of an order from the CPP’s higher organ, the national democrats abandoned the campaign before election time came. As Sen. Salonga would later recall, this desertion so disappointed Ninoy Aquino that he ruled out cooperation with them in the future. Earning the ire of this group, the leaders of the Manila Rizal also faced sanctions from their organization. In the aftermath of this failed `adventurism’, the Committee was temporarily dissolved and its leaders sent to the countryside.[7]

The end of the Marcos regime did not happen only at EDSA in February 1986. Rather, it was a long series of struggles and sacrifices along the way that enabled us to oust the dictator and regained our freedom and democracy. The April 7, 1978 election was so much a part of it.

References

- For this article, the national democrats mentioned are members of the Manila-Rizal Party Committee who did not follow the official Communist Party of the Philippines whose political line disdains electoral exercises and favors instead of armed struggle.

- For an insightful narrative of the dynamics within the Liberal Party that led to the formation of the LABAN (Lakas ng Bayan) campaign, see Jovito Salonga’s book, The Lives and Times of Gerry Roxas and Ninoy Aquino: Their Ancestry and their Achievement (Mandaluyong City: Regina Publishing, Inc. 2010), pp. 61 and ff.

- Former UP President Salvador P. Lopez acted as the periodical’s chair while Rene A.V. Saguisag acted as editor.

- Lopa, Rapa, ed. 2019. To Love Another Day: The Memoirs of Cory Aquino, Makati: The Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation, p.48

- The official results were announced on April 8, just a day after the election.

- Aquilino Pimentel, Martial Law in the Philippines: My Story (Mandaluyong City: Lorraine Pimentel Borghijs, 2006) pp. 185-97.

- For an engaging discussion on the topic, see Malay, Dialectics of Kaluwagan and Abinales, The Left, and other forces.

Works consulted

- Abinales, Patricio N. 1988. “The Left and other forces: The nature and dynamics of pre-1986 coalition politics”. Marxism in the Philippines. Marx Centennial Lectures. Volume 2. Quezon City: Third World Studies Center, University of the Philippines. 19-26

- Lopa, Rapa. ed. 2019. To Love Another Day: The Memoirs of Cory Aquino. Makati: The Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation.

- Malay Jr., Armando S. 1988. “Dialectics of Kaluwagan: Echoes of a 1978 Debate” Marxism in the Philippines. Marx Centennial Lectures. Volume 2. Quezon City: Third World Studies Center, University of the Philippines.

- Montiel, Cristina and Susan Evangelista, eds. 2006. Down from the Hill: The Ateneo from 1972 – 1983. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Pimentel, Aquilino Jr Martial Law in the Philippines: My Story (Mandaluyong City: Lorraine Pimentel Borghijs, 2006)

- Salonga, Jovito. 2010. The Lives and Times of Gerry Roxas and Ninoy Aquino: Their Ancestry and their Achievement. Mandaluyong City: Regina Publishing, Inc.

- Thompson, Mark R. 1996. The Anti-Marcos Struggle: Personalistic Rule and Democratic Transition in the Philippines. Quezon City: New Day.