From Senator to Prisoner: The Story of Ninoy Aquino

Benigno Simeon “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. was known by those close to him as the Young Man in a Hurry because of his fast-paced life. At just 17 years old, Ninoy had already caught the interest of public officials for his achievements. However, his mother Aurora Aquino has also commented that perhaps the reason why Ninoy was always in a hurry was because he knew that his life would be short.[1]

Indeed, Ninoy made waves because he remained a staunch critic of the Marcos regime and its abuses. Even when imprisoned and in self-exile, Ninoy remained steadfast in his beliefs until he was ultimately assassinated. In this exhibit, we look at the life of Ninoy Aquino and how his tale came to inspire many to challenge the dictatorial rule of the Marcos regime.

Early Life

Ninoy Aquino was born on November 27, 1932 in Concepcion, Tarlac to Benigno Aquino Sr. and Aurora Lampa-Aquino. The second of seven children and a part of a prominent land-owning family with a rich political history, Ninoy learned to love being around people. As his biographies describe, Ninoy enjoyed entertaining the family’s visitors and giving speeches even at an early age. [1]

On the other hand, Ninoy was not too fond of going to school.[1] He attended various schools during his elementary years before graduating from St. Joseph’s College. He completed his high school education at the San Beda College and then pursued his college education at the Ateneo de Manila University, where he took AB Philosophy before shifting to AB History. He later took up law at the University of the Philippines, where he joined Upsilon Sigma Phi, the same fraternity as Ferdinand Marcos. Ninoy’s studies, however, were interrupted when he decided instead to pursue a career in journalism.

In 1954, Ninoy married Corazon Cojuangco, the daughter of another land-owning family from Tarlac and a childhood acquaintance of Ninoy.

The Young Man in a Hurry

Ninoy’s claim to fame came when he was only 17 years old. In 1950, Ninoy served as the youngest war correspondent in the Korean War for the Manila Times. For his feats as war correspondent, he was awarded the Philippine Legion of Honor, Degree of Officer by President Quirino.[2] He later served as a foreign-correspondent in Indo-China. During his time as a correspondent, Ninoy was exposed to the ills of North Korea’s communist totalitarian rule and the last moments of French colonialism in Asia.[2]

When Ninoy returned to the Philippines in 1954, he was appointed as personal emissary to Luis Taruc by President Ramon Magsaysay. As personal emissary, Ninoy aided in the negotiations for Taruc’s unconditional surrender, which earned him the Philippine Legion of Honor, Degree of Commander.[1] He would later serve as executive assistant under the Garcia and Macapagal administrations.

From there, Ninoy entered into a long career in politics. The year after his return, Ninoy was elected as mayor of his hometown Concepcion, becoming the youngest mayor at 22. In 1959, he became the youngest vice-governor at 27, and the youngest governor when he assumed the role after the previous governor’s resignation in 1961. He served as governor once more in 1963 before finally winning a seat in Senate in 1967 when he was 35 years old—the youngest of the elected senators. That year, Ninoy was also the only candidate of the Liberal Party to win a seat in the Nacionalista-dominated senate.[1]

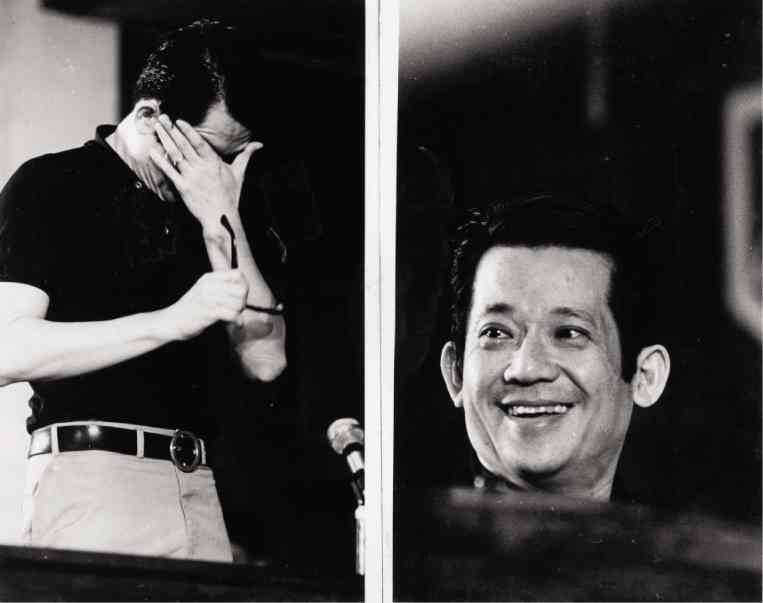

Photo from Ed Santiago

From Senator to Prisoner

As a senator, Ninoy was a staunch critic of the Marcos regime and its abuses. He claimed that the 1967 elections were fueled by “guns, goons, and gold” and stood by the need to criticize to “be free.”[1] In his maiden privilege speech, Ninoy denounced Marcos’ intent of building up a “Garrison state” by “militarizing [the] civilian government offices,” instating “overstaying generals,” and inflating the armed forces budget.[1][2] Ninoy was also critical of the administration’s overspending in infrastructure. He criticized the San Juanico Bridge project as a “luxury bridge to nowhere” and First Lady Imelda’s Cultural Center project, which he dubbed “a monument to shame” in the wake of Manila’s widespread poverty.[1]

Though Ninoy aspired to run for president following Marcos’ second term, his aspirations were crushed when Marcos declared Martial Law. The morning after the declaration, Ninoy was arrested along with other members of the opposition and detained first in Camp Crame and later in Fort Bonifacio. [3] While detained, Ninoy penned ten open letters against the Marcos regime and smuggled them out through Cory to be published in the Bangkok Post; this earned Ninoy and his companion Jose “Pepe” Diokno time in solitary confinement.[3]

On March 12, 1973, Ninoy, along with Pepe Diokno, was brought to a helicopter bearing the presidential seal, handcuffed, and blindfolded. He was transported to Fort Magsaysay in Laur, Nueva Ecija to be put in solitary confinement. As Ninoy recalled:

I found myself inside a newly painted room, roughly four by five meters with barred windows, the outside of which was boarded with plywood panels.[1]

Ninoy was stripped naked and issued only two t-shirts and a pair of underwear to be worn alternately. His other belongings including his wedding ring and his eye glasses were taken away and given to his family without explanation.[1] He and Diokno endured 30 days in solitary confinement.

On August 27, 1973, Ninoy was brought back to Fort Bonifacio where he faced a Military Tribunal on charges of murder, illegal possession of firearms, and subversion.[3] Ninoy, however, refused to participate in the trial, calling it “an unconscionable mockery.”[3] Rather than pleading not guilty, Ninoy delivered a speech denouncing the trial:

Sirs: I know you to be honorable men. But the one unalterable fact is that you are subordinates of the President. You may decide to preserve my life, but he can choose to send me to death. Some people suggest that I beg for mercy. But this I cannot in conscience do. I would rather die on my feet with honor, than live on bended knees with shame.[3]

As a result, hearings were suspended. However, on March 31, 1975, when the tribunal proceeded to re-investigate his case. In response, Ninoy staged a hunger strike to protest the military trial. He refused to eat and subsisted on salt tablets, sodium bicarbonate, amino acids, and two glasses of water a day. Nonetheless, on November 27, 1977, Ninoy was found guilty of his charges and sentenced to death by firing squad.

Ninoy, however, was never executed and was even permitted to run during the 1978 Interim Batasang Pambansa (Parliament) elections. There, he formed the Lakas ng Bayan or LABAN party list, which first popularized the Laban symbol. Ninoy was even given the opportunity to appear on television for his campaign. Unsurprisingly, however, despite the support LABAN garnered from the masses, the party got a zero vote from Metro Manila and lost to Imelda.[3]

Ninoy’s time in prison came to an end in March of 1980 when he suffered from a heart attack in his cell. With permission from the Marcos administration, he sought medical treatment in Dallas, Texas, and later settled down in Newton, Boston, Massachusetts with his family, where he spent his time in self-exile.

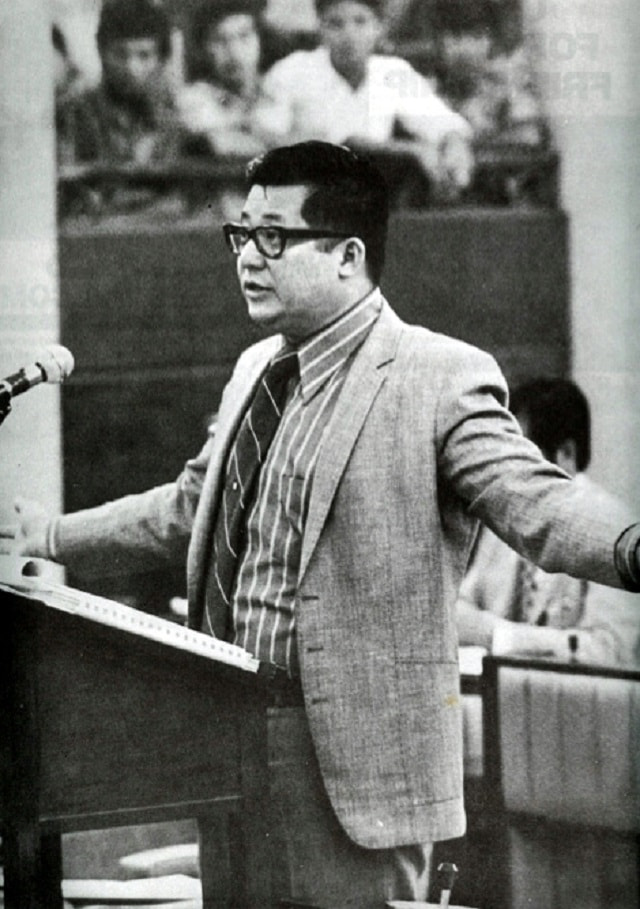

Photo from Philippine Heritage Library

Self-Exile, Assassination, and Legacy

Though Ninoy spent his time in Newton in peace, he kept his mind on the country’s political state. He remained a staunch critic of the Marcos regime even in exile, and it was during this time that Ninoy delivered his often quoted speech in 1981 to the Movement for Free Philippines in Los Angeles:

I have asked myself many times: Is the Filipino worth suffering, or even dying for? Is he not a coward who would yield to any colonizer, be he foreign or homegrown? Is a Filipino more comfortable under an authoritarian leader because he does not want to be burdened with the freedom of choice? Is he unprepared, or worse, ill-suited for presidential or parliamentary democracy? I have carefully weighed the virtues and faults of the Filipino and I have come to the conclusion that he is worth dying for.

Hence, despite protestations from his family and friends, Ninoy ultimately decided to return to the Philippines on August 21, 1983. To these warnings, Ninoy responded with “I’d rather die a meaningful death than lead a meaningless life.”[3] He procured travel documents under the name Marcial Bonifacio and returned to the country on August 21 in hopes of negotiating with Marcos.[3] In anticipation of Ninoy’s arrival, his supporters wore yellow clothes and yellow ribbons and tied yellow ribbons around the trees surrounding Manila International Airport following the song “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree.” Ninoy’s hope of negotiating, however, was never realized; he was shot dead as he was alighting from his plane.

Ninoy’s death ignited a fire among members of the opposition. Many gathered to pay respects to the man who had become the de facto face of the opposition and join the funeral procession. For 11 hours, over a million people marched to Manila Memorial Park to mourn the death of Ninoy; as they marched, the people chanted “Ninoy Ninoy, we love you” and sang “Bayan Ko.” Though Ninoy died before he could realize his hopes, many were inspired to step up and continue his mission to challenge the dictatorship.