From Housewife to President: The Story of Cory Aquino

No account of Martial Law would be complete without mention of Cory Aquino’s journey to presidency. It was Cory’s victory that marked the end of Marcos’ rule, and for many, it also represented the triumph of democracy over dictatorship.

However, never did Cory imagine that she would someday find herself in the country’s highest position. Prior to the assassination of her husband Ninoy, Cory was content with being the supportive wife of the beloved opposition leader. It was public clamor that thrust Cory into the spotlight, with many looking towards her as the remaining beacon of hope during the time.

In this exhibit, we look at the key events in the life of Cory Aquino that led to her monumental victory over Ferdinand Marcos. At the same time, we look to the life of Cory Aquino as a point for reflection on how she was but one of many players in the collective effort that sought to resist the Marcos regime and how she at times had her own share of shortcomings during her presidency. In this light, we hope to ask: How do we understand Cory’s role in the restoration of our country’s democracy given also the controversy of her term as president?

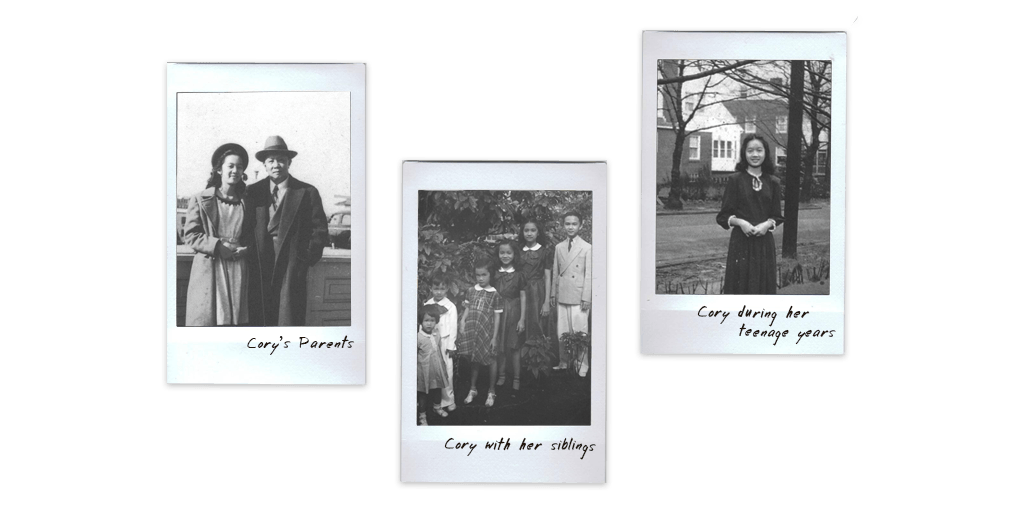

Photos from Cory Aquino’s Autobiographical Website

Early Life

On January 25, 1933, Maria Corazon Cojuangco was born in Tarlac to businessman and former congressman Jose Cojuangco Sr. and pharmacist Demetria Sumulong-Cojuangco. Born into a family of privilege and the fourth of six siblings, Cory grew up in a life of comfort; however, she and her siblings were constantly encouraged by their parents to practice diligence in the event that anything happen to their family fortune. As such, Cory did her best in her studies and topped most of her classes—even graduating valedictorian of her elementary class at St. Scholastica.

After the liberation of Manila badly damaged St. Scholastica’s College, Cory continued her schooling at the Assumption Convent in Paco, Manila. However, shortly after, the Cojuangcos left for the United States, where Cory and her siblings completed their studies. Cory attended high school at the Notre Dame Convent School in New York and later pursued degrees in French and Mathematics at the College of Mount St. Vincent. She returned to the Philippines after graduating in 1953 to pursue law at the Far Eastern University (FEU).

It was at FEU that Cory met once more with childhood acquaintance Ninoy. Though Ninoy had attempted to court Cory in the past, it wasn’t until then that the two fell in love. The year after, Cory halted her studies to marry Ninoy. The two were wed on October 11, 1954, the same day as her parents’ wedding anniversary. For the length of her life, Cory came to know Ninoy not merely as her husband but also as her best friend.

The Politician’s Wife

Cory’s marriage to Ninoy coincided with the beginnings of his political career. Shortly after their marriage and the birth of their first child, Ninoy became mayor of Concepcion, Tarlac. It was then that Cory became more acquainted with the world of politics as she supported her husband despite her initial reservations of being in the public spotlight.

As Ninoy rose through the ranks, later becoming governor of Tarlac and then senator, he began to charm people with his charisma. Cory, on the other hand, preferred to stay in the background. It was clear to her that her role was to take care of domestic affairs while Ninoy handled politics. As Miguela Yap writes in The Making of Cory:

At political rallies, when she had to be present, she invariably declined a seat on the stage, preferring to stay incognito at the back of the audience and listening to the long-playing, nonstop speeches of Ninoy—as he dished out sumptuous accounts of why and how the nation was fast deteriorating economically, while voicing suggestions on solutions to the problems besetting the nation and other political bits and ends.

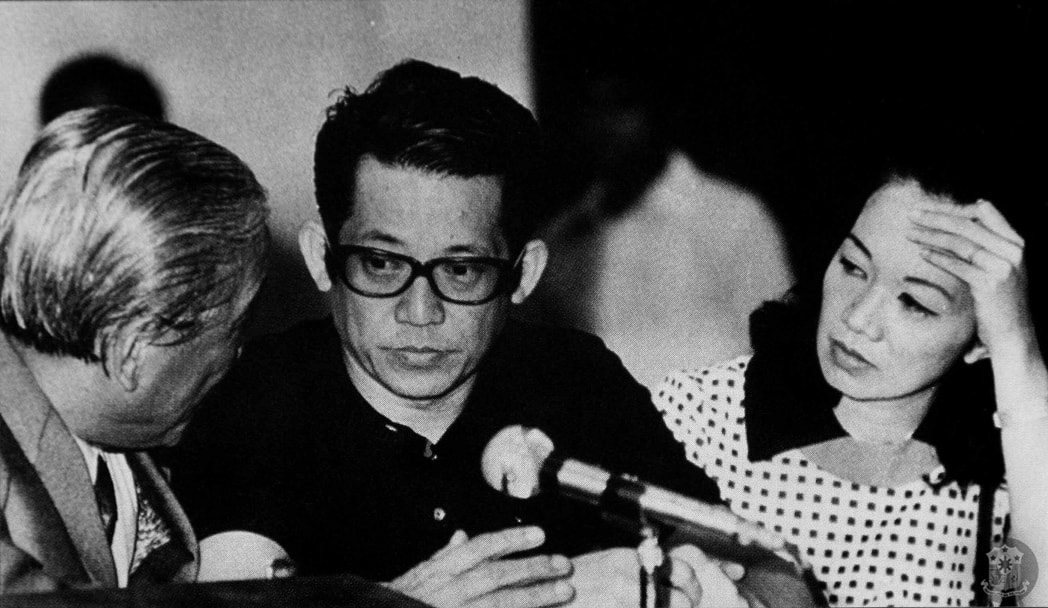

Nonetheless, she supported her husband during his campaigns when needed—courting the voters and handing out leaflets—especially after Ninoy’s incarceration as a political prisoner in 1972. Though Cory initially objected to her husband’s bid during the 1978 interim parliamentary elections, she played an important role in his campaign as she, along with their children, delivered his speeches. Cory also served as Ninoy’s bridge to the outside world, even smuggling out open letters against the Marcos regime to be published in international newspapers. Ironically, these harrowing days for the Aquinos came to an end when Ninoy suffered from chest pains in 1980.

With permission from President Marcos, the Aquinos flew to the United States, where Ninoy sought medical care at the Baylor Medical Center in Dallas, Texas. After, the family settled in Boston, Massachusetts under self-exile, where Cory and her family found respite from the turmoil of Martial Law. The peace the family experienced was cut short, however, when, in 1983, Ninoy decided to return to the Philippines to initiate talks with President Marcos about the political state of the country. As Ninoy was disembarking, he was shot dead on the afternoon of August 21. Shortly after, Cory and her family returned to bury Ninoy; the death of her husband signaled a turning point not just in her life but in the nation’s history.

Laban and The Cory Tidal Wave

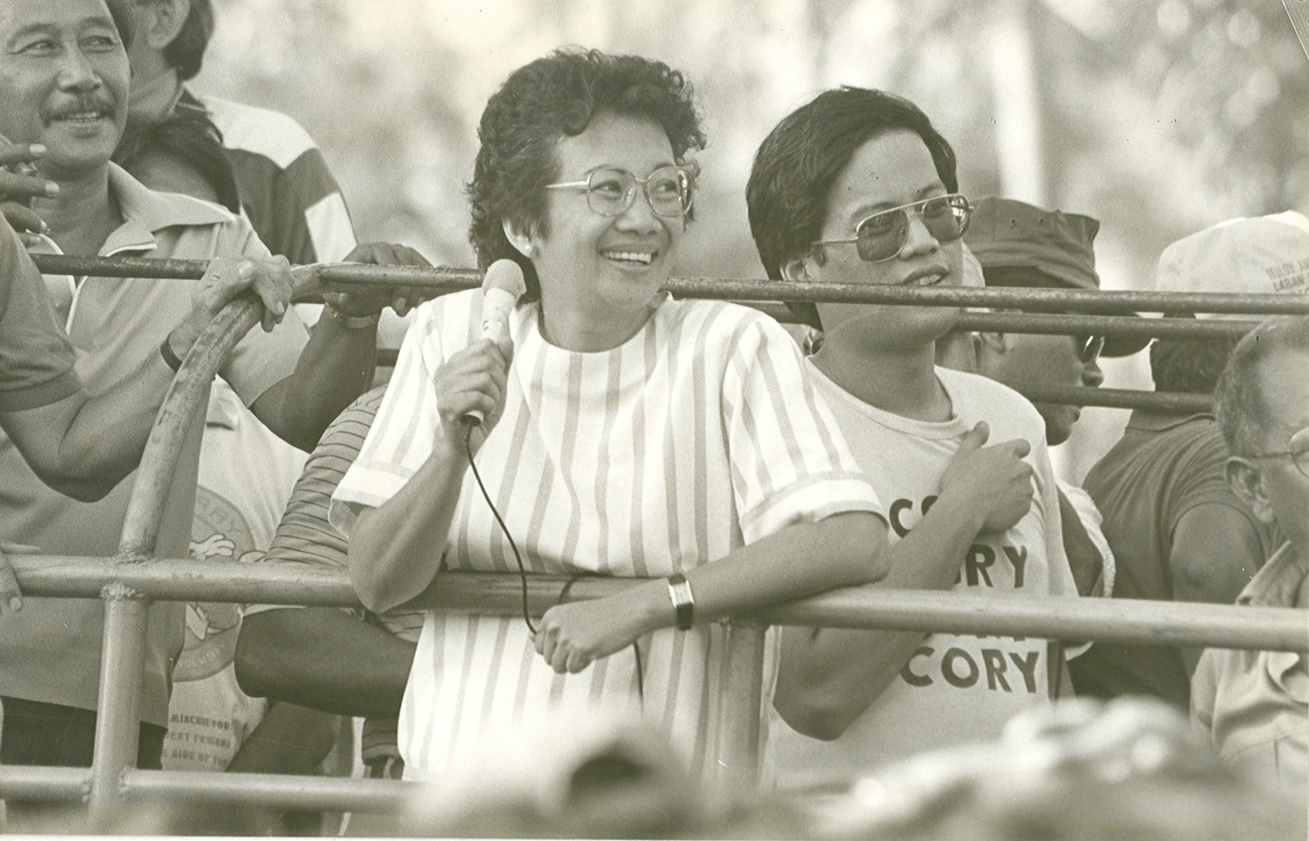

Cory’s composure in the face of her husband’s death became a symbol of hope for many of Ninoy’s supporters enraged by his assassination. Despite her initial shyness, Cory found herself heading to the helm of the opposition as she became increasingly present at demonstrations and rallies.

When Marcos expressed his intent to hold a snap election after mounting international pressure to prove he still had the support of the Filipino people, many turned to Cory despite her inexperience. With her moral uprightness and relative distance from the political scene, Cory was the ideal candidate to challenge Marcos. Hesitant to run, however, Cory set forth two conditions: first, that the opposition gather the signatures of one million Filipino voters to draft her, and second, that President Marcos sign the resolution to call for a snap election.

When the snap election was officially announced for February 7, 1986, the Cory Aquino for President Movement headed by Chino Roces saw overwhelming support. All in all, the movement gathered 1.2 million signatures well ahead of its deadline. With her conditions met, Cory became the official opposition candidate for president. Her allies later convinced long-time friend of Ninoy Salvador “Doy” Laurel, who had also intended to run for president under the United Nationalist Democratic Organization (UNIDO), to concede his candidacy and instead run as Cory’s vice president.

Now set to run as the presidential candidate of a unified opposition, Cory began her campaign. Marcos, on the other hand, sought to discredit his opponent, saying she was “only a woman” and “walang alam.” To this, Cory responded: “I have to admit I have no experience in lying, cheating, stealing, killing political opponents.”

Despite Marcos’ attempts to smear his opponent, Cory was met with overwhelming support. It was during Cory’s campaign trail that the laban sign was popularized; it had first appeared during Ninoy’s campaign under the Lakas ng Bayan (LABAN) party during the 1978 interim elections, but later became the symbol of opposition during the EDSA Revolution.

The 1986 snap election was rife with reports of cheating, vote buying, and violence; as many as 20 voters were registered under identical names and the list of voters was said to be padded with about 1.5 million spurious voters. Unsurprisingly, Comelec declared Marcos the winner. However, an independent count done by the National Citizen’s Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL) declared that it was in fact Cory who had won.

In protest of Marcos’ declared victory, Cory and her allies launched a civil disobedience campaign. She encouraged the people to boycott crony-owned businesses and media, to delay their payment of utility bills, and to hold a strike the day after Marcos was scheduled to take his oath of office. Alongside Cory, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines released a pastoral letter condemning the election as unparalleled in fraudulent conduct.

The subsequent defection of Juan Ponce Enrile and Fidel V. Ramos to the opposition further galvanized the people towards the eruption of the EDSA Revolution. With pressure coming from all sides, Marcos and family fled the Philippines for Hawaii, and on February 25, 1987, Corazon Aquino was sworn into office as the 11th president of the Philippines and its first female president. In the same year, she was declared as TIME magazine’s Woman of the Year.

Presidency and Legacy

It was under the Aquino administration that the 1987 Constitution was ratified; the constitution limited the presidential power to declare martial law. The administration also established the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), a committee dedicated to the recovery of the Marcos ill-gotten wealth. For many, Aquino’s administration signified the restoration of democracy in the country as it attempted to restore civil liberties and released the political detainees of Martial Law.

However, the Aquino administration was severely hampered by various factors. Beyond the economic blows dealt by Martial Law, the Aquino administration also had to contend with the worsening communist-led insurgency and the political infighting. Disagreements over how to handle the communist insurgency led to the resignation of Defense Minister Enrile[1], and from 1986 to 1990, members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines organized six plots to overthrow President Aquino. The worst of these plots was the day-and-a-half August 1978 coup attempt led by Col. Gringo Honasan, which left 53 dead and more than 200 wounded, many of whom were unarmed civilians.

Furthermore, despite all its attempts to address the most pressing problems of the country, the Aquino administration ended its term still facing the problems of widespread poverty, high unemployment rates, and stunted economic growth after the many coup attempts. For critics of Cory and even her former supporters, many of the problems her administration faced stemmed from her political indecisiveness.

Following the end of her term, Cory remained active in the political scene, voicing dissent against government policies that appeared to threaten democracy, such as Ramos’ and Estrada’s attempts to amend the constitution to extend their terms, up until her death on August 1, 2009. Though remembered by many as the “mother of Philippine democracy,” Cory insisted that it was by the power of the Filipino people that democracy was restored.

References

-

Briscoe, D. (1986, January 2). Corazon Aquino’s loose campaign attracts thousands. The Times-News. Retrieved here.

-

Fact-Finding Commission (1990). The final report of the Fact-finding Commission. Retrieved here.

-

Kalaw-Tirol, L. (2000). Public faces, private lives. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

-

Nokes, R.G. (1986, February 11). Tainted Marcos win could hurt relations. Times Daily. Retrieved here.

-

Sanger, D. (1992, June 10). Cory’s deeds marred by her indecisiveness. New Straits Times. Retrieved here.

-

Yap, M. (1987). The making of Cory. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

-

Photos from the Presidential Museum & Library